Keep calm and stay angry. ![]()

This is a pandemic journal entry, sans the clerkship struggles and the quarantine cooking.

𝗪𝗵𝗮𝘁 𝗰𝗮𝗻 𝗰𝗵𝗮𝗻𝗴𝗲 𝗶𝗻 𝟭𝟬𝟬 𝘆𝗲𝗮𝗿𝘀?

For Avatar Aang, a lot [1]. For the Philippines, a lot and nothing at all. Somehow.

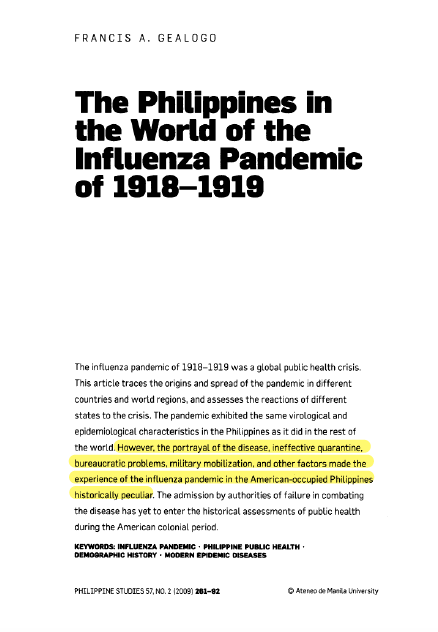

I was reading through a 2009 journal article entitled “𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘗𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘪𝘱𝘱𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘞𝘰𝘳𝘭𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘐𝘯𝘧𝘭𝘶𝘦𝘯𝘻𝘢 𝘗𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘮𝘪𝘤 𝘰𝘧 1918-1919” written by Francis A. Gealogo [2]. I thought a trip to the past would help me feel more forgiving of the present. Surely, with all the advances in medicine and with our people-power-driven democracy, we’d have it better than the time of our mothers’ mothers’ mothers.

But no. The abstract reads, “the portrayal of the disease, ineffective quarantine, bureaucratic problems, military mobilisation, and other factors made the experience of the influenza pandemic in the American-occupied Philippines historically peculiar.”

Sounds familiar? Swap America with our bourgeoisie or Ch*na, and it’s pretty much the same.

There are apparently plenty of interesting notes about the 1918 influenza pandemic, which led to at least 50 million deaths worldwide (probably grossly underreported). Almost universally, the spread of the epidemic had a racialized character. But there’s a section that really inspired me to reflect–

‘𝗣𝗿𝗼𝗯𝗹𝗲𝗺𝘀 𝗶𝗻 𝗖𝗼𝗺𝗯𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗣𝗮𝗻𝗱𝗲𝗺𝗶𝗰 𝗶𝗻 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗣𝗵𝗶𝗹𝗶𝗽𝗽𝗶𝗻𝗲𝘀’

From page 281 onwards, Gealogo identified at least four problems related to the management of the disease across the archipelago. These included (1) personnel challenges and political infighting, (2) failure of quarantine, (3) military mobilisation campaigns and other concentration points, and (4) the portrayal of the disease in the Philippines. In the spirit of reviewing literature, I was curious whether the same or similar problems are present in the Philippine’s response to the coronavirus pandemic of 2020.

𝗠𝗶𝘀𝗺𝗮𝗻𝗮𝗴𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁, 𝗽𝗼𝗹𝗶𝘁𝗶𝗰𝗮𝗹 𝗶𝗻𝗳𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗴, 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝘀𝗮𝗰𝗿𝗶𝗳𝗶𝗰𝗶𝗮𝗹 𝗵𝗲𝗮𝗹𝘁𝗵 𝘄𝗼𝗿𝗸𝗲𝗿𝘀

𝗙𝗜𝗥𝗦𝗧, Gealogo discussed how retention of personnel was challenged by “resignations, retirement, death, and the military exigencies of the First World War” (p. 281). Administrative crises and politicking challenged the performance of health campaigns. Gealogo cited how the national Director of Health (then Surgeon John D. Long) resigned during the tail-end of the second wave in 1918. He was replaced by the first Filipino acting Director of Health, Dr. Vicente de Jesus.

This reminds me of several things. One, the transition reads like a racialized form of the glass cliff [3]. It’s the phenomenon when women —or in this case a member of the racial political minority— assumes a leadership role during a period of crisis, since the chance of failure is highest. Dr. Vicente de Jesus sounds like the fall guy.

I’m not certain how this will ever be a problem in the current Philippine government, as nobody in any position is brought up to full accountability anyway.

The racially-charged criticism of the pandemic response by Americans against the Filipino-health service is discussed in this YouTube video by Kirby Araullo entitled ‘𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘚𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘴𝘩 𝘍𝘭𝘶 𝘗𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘮𝘪𝘤 & 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘗𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘪𝘱𝘱𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴! [𝘉𝘭𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘍𝘪𝘭𝘪𝘱𝘪𝘯𝘰𝘴?]’ [43]. According to Araullo, Americans later blamed Filipinos for mismanagement of the response in 1918, despite the fact that Americans were at the helm at that time. The Americans blamed the Filipinos, especially the lower class, for contributing to the spread of the disease –through their hygiene practices, allegedly bad parenting, and lack of sanitation. This classist blame game reminds me of influencer Cat Arambulo, and her infamous “Why don’t you motherf*ckers just stay at home?” directed at the disenfranchised [44].

Two, this reminds me of how I’ve never heard of the influenza pandemic in the context of the Philippines before this reading. I can only remember few distinct themes in history classes on the American occupation: the rise of public education, the transformation of vaudeville and zarzuela, and the first world war. Americanization of media and culture is also a central theme of ‘𝘕𝘦𝘸 𝘠𝘰𝘳𝘬𝘦𝘳 𝘪𝘯 𝘛𝘰𝘯𝘥𝘰’ written by Marcelino Agana Jr. in 1956. I think I directed it in first year high school (?). I digress.

In the second edition of ‘𝘈 𝘓𝘦𝘨𝘢𝘤𝘺 𝘰𝘧 𝘗𝘶𝘣𝘭𝘪𝘤 𝘏𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘵𝘩: 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘋𝘦𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘏𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘵𝘩 𝘚𝘵𝘰𝘳𝘺’ published in 2014, a whole chapter covers the ‘Filipinization of Health Services from 1918-1941’ [4]. DOH mentioned the government under Francis Harrison (which featured greater Filipino participation), cited the cholera epidemic of 1902-1905 as the deadliest epidemic in Philippine history (it was), and devoted only one sentence to the rise to position of Dr. Vicente de Jesus. Somehow, despite the fact that the Philippines had a 40.79% death rate in the 1918 pandemic, leading to an estimated 85,000 deaths, the influenza pandemic of 1918 was not mentioned.

The influenza pandemic was overshadowed by the changes brought about by the first World War. It was also swallowed by the sweeping changes made to combat smallpox, cholera, and tuberculosis. In the end, 100 years later, the influenza isn’t even a footnote in our collective consciousness of health history.

Three, this reminds me of our current problem in human resources, including job mismatching, poor public communication, and lack of health workers. In the early 20th century, the General Hospital was under the Secretary of the Interior, and the Bureau of Public Health was adjacent to the Department of Public Instruction (now Department of Education). This sounds exactly like a national task force against COVID-19 led by the Department of National Defense secretary and other former army generals [5].

In what are probably efforts to inspire confidence and competence in the middle of a pandemic, we also saw a change in the presidential spokesperson from the unintelligible Panelo to a condescending Roque [6]. In the same news cycle, we saw more than two thousand health care workers testing positive for coronavirus, with dozens in mortality [7]. We witnessed the selective OFW deployment ban, which barred health professionals from working abroad [8]. It’s a mess. I’m a mess.

The Filipino-led health service of 1918 had to struggle with a virulent epidemic along with extreme personnel shortage. The Philippines was later understaffed thanks to World War I (Araullo, 2020). Around this time, there were only 930 nurses for a population of 10.5 million Filipinos (DOH, 2014). That’s a ratio of 1:11,000. As of 2017, we have a ratio of about 1:1100 [9]. Infinitely better, but far from the ideal 1:12 toted by the DOH.

But who can blame our ‘frontliners’? Even though our hospitals and ICUs should be the last line of defense, we’ve created a society where doctors, nurses, orderlies, and caregivers have to be the first to sacrifice, the first to defend, and even among the first to die. We also created a society where ambulance drivers can get harassed near their own homes [47], a hospital staff member could have been blinded by bleach splattered by a gang in Sultan Kudarat [48], and medical frontliners were either being evicted by their landlords or denied entry to their barangays [49]. Not to mention the continuing terror of doctors and nurses protecting themselves with only literal garbage bags [50].

Why did our defense of frontliners have to come from fashion designers [51] and private donations? I still can’t believe the DOH tried to solve this by offering a P500 allowance for volunteer health care workers [37].

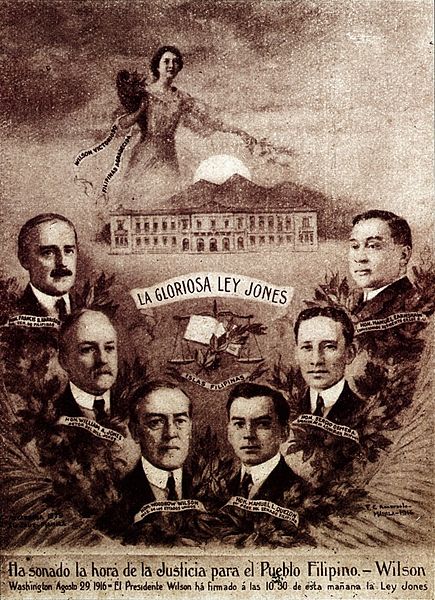

Gealogo also similarly wrote that critics of the 1918 pandemic response blamed different colonial officials in line with the racialized political issues of that time. We had to cram the American occupation in the last quarter of first-year high school history class, but I’m fairly sure the Jones Law was about the withdrawal of American sovereignty from the Philippine islands. The political fighting was probably crazy dirty.

The intrusion of overt politicking into the service of otherwise competent leaders sounds familiar, e.g., the absolutely wasteful NBI summons on Pasig City Mayor Vico Sotto [10], and the similarly baffling (and later abandoned) accusation by the PACC commissioner against Vice President Leni Robredo [11]. The absolutely ill-timed and politically-charged franchise battle against media corporation ABS-CBN [38], ignores all press freedoms, goodwill, and common sense, and sets the stage for select legislators to curry favor from the public.

Fernando Amorsolo. La Gloriosa Ley Jones, 1916.

𝗙𝗮𝗶𝗹𝘂𝗿𝗲 𝗼𝗳 𝗾𝘂𝗮𝗿𝗮𝗻𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗲, 𝗴𝗿𝗮𝗻𝗱𝘀𝘁𝗮𝗻𝗱𝗶𝗻𝗴, 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗹𝗮𝗻𝗴𝘂𝗮𝗴𝗲 𝗴𝗮𝗺𝗲

𝗦𝗘𝗖𝗢𝗡𝗗, the quarantine system in the Philippines failed to stop the spread of the 1918 influenza, though quarantine was otherwise effective in Australia (p. 269) and American Samoa (p. 270). “Despite the bravado pertaining to the institutionalisation of the quarantine system,” Gealogo wrote, “the outbreak of the pandemic indicated that such a system failed to check the entry of the disease and its spread in the archipelago (p. 282).”

Our quarantine system has indeed become a meme. This is the government that denied a lockdown in the middle of an enhanced community quarantine [12]. What are words but playthings for powerful men?

If it weren’t for a dedicated Wikipedia entry, I would have forgotten all the incarnations of the quarantine so far [13]. As of writing, we have the original community quarantine (the OG), the enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) the extreme or extensive enhanced community quarantine (EECQ), the general community quarantine (GCQ), the modified general community quarantine (MGCQ), and my personal favourite — the calibrated community quarantine (CCQ) of Cavite.

May we never forget that our quarantine measures included non-contact body thermometers reading out 35.4 celsius (???), more than 9000 college students stranded in Metro Manila for at least 2 months [14], more than 20,000 repatriated OFWs stuck aboard cruise ships and hotels [15], actual torture of curfew violators by making them sit under the sun for an hour (“harmful exposure to the elements such as sunlight and extreme cold” under RA 9745) [16][17], and Marlon Dalipe, who walked five days from Alabang to Camarines Sur, because bus rides were suspended and he couldn’t come home [18]. He was one among many. I remember thinking of how my grandmother fled through the forests of Laguna for days and days to escape the invading Japanese. It’s 2020. How are people still forced to walk kilometres for their own health and safety?

And of course, while the rest of the world advocates “Test, Treat, Track” alongside quarantine, the Philippine government decided to offer nothing. Nothing!

Choose your poison —either the government reneging on a promise to roll out targeted mass testing by April 14 [19], Roque throwing the private sector under the bus by making them responsible for mass testing [20] and the subsequent patronising drama over alleged misinterpretation [21], or the mental gymnastics needed to accept the veracity of DOH’s COVID-19 data, from their wobbly definitions of “pandemic waves versus epidemiological waves” [22] to their invented and probably arbitrary “fresh versus late cases” delineation [23]. I am not the only one who sees epidemiologists like Dr. Edsel Salvana as condescending, pseudo-intellectual, biased mouthpieces [39]. #MassTestingNow

I guess I can also confidently say the curve is flattening, if I squint really hard and get paid millions of pesos under the table.

𝗦𝗼𝗰𝗶𝗮𝗹 𝗱𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗮𝗻𝗰𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗹𝗮𝗰𝗸 𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲𝗼𝗳

𝗧𝗛𝗜𝗥𝗗, the spread and virulence of the disease was exacerbated by the concentration of certain groups. The “military mobilisation campaigns of the colonial administration in preparation for an anticipated participation of the Philippines in the First World War” (p. 281-282) included a three-month training course of officers and troops in Rizal. In the middle of a pandemic.

The mobilisation of draftees and their concentration in a training camp created a ‘convenient breeding ground’ for the influenza virus. According to Gealogo, the government at that time expanded a sort of quarantine around Camp Claudo to include other localities, designated the ‘camp Claudio extra cantonment zone’. The entire district was relabelled a ‘working quarantine camp’. However, Gealogo argued that the efforts to control the epidemic, e.g., sanitation, distribution of medicines, education, cleaning and monitoring, were likely less for the benefit of the nearby localities, and more for (a) the protection of the military draftees and (b) the American colonial sanitary order.

Military mobilisation for the sake of an impending world war isn’t a thing in 2020, so for a nanosecond I thought I finally found a problem in 1918 that wouldn’t apply to our current crisis. Hurrah!

But then I remembered that we have Rodrigo Duterte as our president, who actively marketed his links to the Davao Death Squad and who has championed a bloody drug war [24]. This is the government that debated about buying US-made versus Turkish-made attack helicopters for the Philippine Air Force in the middle of a pandemic [25], under the flimsy excuse of fighting against internal insurgency. This is the country where the military –mobilised to man checkpoints– wore camouflage uniforms and carried assault rifles [26], while flouting social distancing recommendations in their attempt to help commuters [41].

If the parallel is to compare the government’s sense of priority and the power of the military, then 2020 is still as bad as it gets. Other countries are fighting for #BlackLivesMatter and against police brutality. Filipinos are obediently stuck at home or at work, watching congress pass HB 6875 — the “Anti-Terror Bill”, which President Duterte marked as urgent [27]. Literally everything is urgent, except for this pandemic. #JunkTerrorBillNow

Aside from the militarisation campaign and the related training camps, Gealogo’s research also found other centers of spread in prisons, leper colonies, and schools.

Though schools have thankfully been closed for the protection of students, teachers and staff since March 2020, our prisons can’t be as fortunate. You would think it obvious, but I don’t think anyone thought of the Bilibid Prisons in the early days of coronavirus. Horrifyingly, the New Bilibid Prison has a 335% congestion rate, which is way over actual holding capacity. A report says several dozens of people have died with unclear causes of death —and with no testing [28].

But our schools also won’t stay safe for long. The University of the Philippines, which was at the forefront of the pandemic response along with the General Hospital, suspended their second semester for school year 1918-1919 [42]. Today, online classes continue to the detriment of the 99%, and the Department of Education is likely to reopen classes without enough precautions or measures for accessibility. This is supported by DepEd’s ridiculous online survey on the opening of classes, which obviously had biased results showing that majority of students and teachers have access to the Internet [33]. This is an example of bad study design and sampling bias.

𝗘𝗽𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗺𝗶𝗼𝗹𝗼𝗴𝘆 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗱𝗶𝘀𝗲𝗮𝘀𝗲 𝗰𝗼𝗻𝘁𝗿𝗼𝗹 𝘄𝗵𝗼

𝗙𝗢𝗨𝗥𝗧𝗛 𝗔𝗡𝗗 𝗙𝗜𝗡𝗔𝗟𝗟𝗬, Gealogo highlighted a peculiarity in the Philippine response, seen even until the aftermath of the 1918 pandemic. From the start until the end, the Philippine government consistently insisted on an “autochthonous origin” (p. 288). They claimed that the influenza pandemic was largely local in origin [46].

Health officials were comfortable in asserting that the influenza pandemic —literally a worldwide pandemic— was native to the country, and that “after the importation of cases it only assumed a more severe form” (p. 273). This is likely rooted in racism as well, with the premise of dirty Filipinos. In the global stage of 1918, the Philippines was singular in its arrogance and wilful blindness to common sense.

By localising the disease as ‘trancazo’, by insisting that cases were occurring before the arrival of foreign ships, by ignoring the origins of the disease as a global pandemic, I would argue that the Philippine Health Service of 1918 basically said goodbye to epidemiological investigation and contact tracing, ultimately undermining every other effort to combat the disease medically and systematically. It almost sounds familiar.

It is a special kind of oppressive, non-scientific narrative our government can apparently make in times of pandemic.

𝗬𝗼𝘂 𝘄𝗼𝘂𝗹𝗱 𝘁𝗵𝗶𝗻𝗸 𝘁𝗵𝗮𝘁 𝗶𝗻 𝟭𝟬𝟬 𝘆𝗲𝗮𝗿𝘀, the Philippines could have looked back at the 1918 influenza pandemic —plus every subsequent crises— and changed for the better. Maybe we could have had a thriving health care industry with well-compensated professionals and positive health-seeking behavior. Maybe we could have had better, cheaper and more humane public transportation systems. Maybe our prisons could have more space, or our justice system could have more compassion for the poor. Maybe our Internet wouldn’t be as shit. Maybe, maybe, maybe.

𝗜𝗻𝗳𝗶𝗻𝗶𝘁𝗲 𝗽𝗿𝗼𝗯𝗹𝗲𝗺𝘀 𝗶𝗻 𝟮𝟬𝟮𝟬

The journal article I read did not discuss the economic impact of the 1918 influenza pandemic. It also did not mention capitalism (along with corruption and the class system) as the source of all evil. But for today’s pandemic, even without parallels, I will have to write:

- Senator Koko Pimentel violating all protocols and the Bayanihan Law by visiting a hospital, going to a supermarket and attending a party (not necessarily in that order) while under monitoring for COVID-19 [29]

- Quezon City officials beating and dragging a fish vendor for failing to wear a face mask [30]* OWAA Deputy Administrator Mocha Uson sharing fake news, in violation of the Bayanihan Law, but she’s getting away with saying it was an ‘honest mistake’ [31]

- The warrantless arrest of a public school teacher over an obviously hyperbolic tweet ‘threatening’ President Rodrigo Duterte, which was ruled as “cured” (i.e., allowed) by the DOJ [32]

- Police chief Major General Debold Sinas breaking quarantine, mass gathering protocols, and social distancing practices with the excuse that it was only a mañanita, whatever that is, and with the protection of his position [52]

- Trigger-happy policemen fatally shooting veteran Winston Ragos just for… having a quarantine pass? carrying a bag? and later an alleged magical .38 caliber pistol [53]

- A president who shouts out to China for help, for gratitude, for anything…* Our mounting debt, which is edging closer and closer to an additional trillion pesos within just a few months (!) [45], with nothing to show for it but a president who flies to Davao for “official duties” in the middle of a quarantine [35]

- And house bill 7295, which raises the allowed campaign spending limits of candidates and political parties [36]

- Briefings at 12 midnight! Never again!

It’s been a long 80 days.

I initially wrote this down as my 𝗽𝗮𝗻𝗱𝗲𝗺𝗶𝗰 𝗷𝗼𝘂𝗿𝗻𝗮𝗹. In the early days of this 80-day lockdown, there were several articles and social media posts telling people to “write your thoughts down”. Our experiences in 2020 will define the generations to come. Our children’s children will ask us how it was to live through a pandemic and a revolution. In a hundred years, someone will write a journal article entitled, “𝘗𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘪𝘱𝘱𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘞𝘰𝘳𝘭𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘊𝘰𝘳𝘰𝘯𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘳𝘶𝘴 𝘗𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘮𝘪𝘤 𝘰𝘧 2020”.

As people rally out in the streets of America and Hong Kong and Japan and London and Brazil against racism and police brutality, as Filipino commuters continue to struggle with the poor transport system, walking kilometres and betting their jobs by hitchhiking, as Filipino workers continue to grow hungry, as the Philippine government continues to do everything but mass testing…

I hope. And look towards the hundred years to come.

This post is also public on Facebook.

𝗙𝗼𝗼𝘁𝗻𝗼𝘁𝗲𝘀

[1] If you haven’t watched Avatar: The Last Airbender, please do yourself a favour. It’s on Netflix.

[2] Gealogo, F. (2009). The Philippines in the world of the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. Philippines Studies 57(2):261-292. Access: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42634010

[3] https://www.vox.com/2018/10/31/17960156/what-is-the-glass-cliff-women-ceos

[4] Department of Health. (2014). A legacy of public health: the Department of Health story, 2nd ed. Retrieved from https://www.doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/publications/The%20Legacy%20Book%202nd%20Edition_0.pdf

[5] https://news.mb.com.ph/2020/03/25/lorenzana-heads-covid-19-national-task-force/

[6] https://www.rappler.com/nation/257772-harry-roque-returns-duterte-presidential-spokesman-april-2020

[7] https://www.rappler.com/nation/261271-health-workers-coronavirus-cases-philippines-may-18-2020

[8] https://www.cnn.ph/news/2020/5/14/New-hires-OFWs-health-worker-ban.html

[9] Nurse Statistics in the Philippines as of 2018 (or latest). PDF retrieved from: https://www.foi.gov.ph/requests/aglzfmVmb2ktcGhyHQsSB0NvbnRlbnQiEERPSC01NTMwNzAzOTUxMTEM

[10] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1255432/vico-asks-nbi-to-clarify-possible-violation-of-bayanihan-law

[12] https://news.mb.com.ph/2020/03/22/palace-denies-report-of-alleged-imminent-lockdown-over-covid-19/

[13] Thank you Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_community_quarantines_in_the_Philippines

[14] https://www.rappler.com/nation/260838-stranded-students-go-home-hatid-estudyante

[16] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1248527/paranaque-village-chief-accused-of-torturing-curfew-violators

[17] https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2009/11/10/republic-act-no-9745/

[22] https://news.mb.com.ph/2020/05/21/doh-official-apologizes-over-first-wave-second-wave-confusion/

[24] https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/09/07/philippine-president-rodrigo-dutertes-war-drugs

[27] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1284472/duterte-certifies-as-urgent-anti-terror-bill

[30] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1266426/labor-group-on-beating-of-qc-authorities-to-a-fish-vendor

[31] https://www.rappler.com/nation/261236-mocha-uson-response-nbi-summon-ppe-photo

[34] https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Coronavirus/Duterte-orders-Manila-lockdown-from-Sunday

[35] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1276587/dutertes-davao-trip-part-of-official-duties-says-roque

[36] https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2018/05/22/house-passes-bill-campaign-expenses-elections.html

[38] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ABS-CBN_franchise_renewal_controversy

[39] https://opinion.inquirer.net/128475/the-growth-rate-in-covid-19-cases

[40] Someone helpfully uploaded a script of the New Yorker in Tondo online. https://sirmikko.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/new-yorker-in-tondo.pdf

[42] https://twitter.com/upsystem/status/1257932970888802304

[43] Araullo, K. (2020, Mar 25). “The Spanish Flu Pandemic & the Philippines! [Blame the Filipinos?]”. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jVJcCeKatgE

[44] https://ph.news.yahoo.com/tone-deaf-influencer-cat-arambulo-050136422.html

[46] Even more science and history time! There is no universal consensus on the origin of the 1918 influenza virus. ‘Spanish Flu’ can be due to xenophobia (Araullo, 2020) or the fact that Spain was the only one really reporting the flu because it was neutral in World War I (Gealogo, 2009) until November 1918.

Popular and more credible theories include France (contemporary Spanish newspapers at that time called it the “French flu”). Early 2000s research pointed to a January 1918 outbreak in Kansas. A recent 2019 article synthesised current knowledge about the pandemic and used indirect methods such as phylogenetics to narrow down the origin. The authors pointed to inconsistent standards in epidemiological reporting as a confounder in determining geographic origin. Sensationalist reporting also made contemporary public documentation unreliable.

However, the most persuasive evidence, i.e., phylogenetic analyses of avian-like genomic segments, point to a North American origin, many years prior to 1918. (This also supports the hypothesis on acquired immunity of the older population against the 1918 influenza).

Worobey, M., Cox, J. & Gill, D. (2019). The origins of the great pandemic. Evolution, Medicine and Public Health, 2019 (1): 18-25. https://doi.org/10.1093/emph/eoz001

[47] https://www.rappler.com/nation/256888-frontliner-attacked-quezon-coronavirus-fears

[48] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1250393/bleach-thrown-at-hospital-worker-in-sultan-kudarat

[49] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/attacked-underpaid-filippino-nurses-battle-virus-200402010303902.html

[50] https://www.businessinsider.com/photos-show-doctors-nurses-improvising-due-to-lack-of-ppe-2020-4

Say something back.