Deep in my heart is a universal truth: I need a regular dose of art museum visits or I’ll wither. Is art a drug? Or a coping mechanism against the dregs of life? This blog post is dedicated to all our museum stops during our Europe Tour last April 2025.

The Louvre, Musée d’Orsay, and Museo Nacional del Prado gave me enough battery to survive the first six months of 2025. (But I’ll still try to post the little museum and gallery refueling stops I did in Manila the last few months some other time).

To more art adventures!

Never the same museum twice

Going to a museum is a lot like reading a book, or watching a play —it’s never the same experience twice.

Galleries evolve, curators change. But it’s also the visitor who transforms. I am certainly a different person from the 15-year-old girl who had the privilege of visiting the Louvre that first time.

I’m also traveling with my own money, except for the airfare and lodgings that my mom graciously sponsored us in celebration of her 60th birthday, so it’s also a little more intentional.

.

.

When I was fifteen, I didn’t have the resources (or frankly, the interest) to learn more about the masterpieces in the Louvre. It was only through the decade that followed that I really pursued aestheticism as a hobby. And now I think I’m more intentional about the moments I spend standing in front of canvasses.

.

.

I’m waxing poetic and feeling a little nostalgic for the past. To be honest, this post is also inspired by the theme of this year’s International Museum Day. “The Future of Museums in Rapidly Changing Communities”. Having traveled and visited museums frequently over the years, innovations in museum culture cannot be ignored. (Though I’m still not convinced by the epidemic of ‘digital art installations’ and ‘immersive art museums’.)

Despite all that’s different today, the bones of European museums remain much the same. Art that’s been gathering dust and applause for 500 years will take a little more than just a few decades to ‘rapidly change’.

And regardless of the time, the setting, or my age –art continues to heal.

Art is a wound turned into light.

Georges Braque (1882-1963)

The Louvre

The national art museum of France and the most visited museum in the world remains a pleasure (and a workout) to visit. It’s home to some of the most canonical works of Western classical art, including the Mona Lisa, Venus de Milo, and Winged Victory. Apparently it would take 100 days to see every single piece on display.

The entry queues appear doubly long, even with timed entry tickets, and Da Vinci’s La Joconde is now absolutely dwarfed by the crowd. The perimeter also feels farther away from the painting, so it takes effort to appreciate the sfumato. And yet we clamor for her, 10/10.

Her small frame has a presence which dwarfs the other paintings that line the hall.

.

.

.

.

What I’ve always loved about art is its cyclical, iterative, and transformative quality. “Art is both the progeny and the progenitor” is a pretentious statement I came up with for my high school art portfolio, and I still stand by it. Without the Mona Lisa, however overrated it might seem, thousands of other works would not have been made the same way. This blog post would certainly be different.

(My short video for this post would also be different. Stream Mona Lisa by j-hope.)

I think anyone interested in visual arts and history would need to visit the Louvre at least once. The first time is to be overwhelmed, and the second time to more seriously look at the details. The giant museum is more than just its paintings; it’s also the sculptures, the lighting, and the palatial architecture.

Compared to my younger self, I’ve grown. I own a few more coffee table books on traditional art, and a tiny collection of local works. I’ve spent several hours spent on the Google Arts&Culture app and YouTube.

Now I can appreciate the placement and the beauty of the Winged Victory of Samothrace, situated right on top of the grand staircase in the Denon Wing. You can hear the sea as it breaks through the waves for a long-sunken warship.

It was also in Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s Apesh*t music video, which is arguably a work of art in itself. Again: adaptation and iteration.

.

.

*This is also to recognize the call of Greece for the return of this Hellenistic sculpture. The only true downside of classical museums in Europe is their history of thievery and continuing audacity.

There were also some rooms I felt like I was discovering for the first time. The Galerie d’Apollon is breathtaking on its own right, with iconic and finely detailed portraits and scenes lining the walls. The “petite” gallery also houses the French crown jewels.

.

.

The intersection of art and history is always a point of interest for me. Before the age of the Internet (and the accessibility of global news that came with it), the world was much smaller. Political and social events had to be truly controversial or important to be immortalized through art.

For one thing, it’s interesting to see how the accessibility of art has changed over the years. These intricate and elaborately-decorated walls used to be the private domain of the rich and titled. The enfilades leading to inner galleries reflected the power of intimacy and privacy, or its reverse.

But also, the subject of art has changed from biblical representations to royal portraiture to social and genre paintings. The Raft of the Medusa (1818-1819) by Théodore Géricault is an icon of French Romanticism that I only discovered some time in the last few years. Probably in medical school? The desperate poses and the dramatic composition depict the aftermath of the wreck of the ship Méduse. Of the 150 or more people that were set adrift on the raft, only 15 survived —by resorting to cannibalism.

With the 1816 wreck fresh on people’s minds, I can only imagine the controversy and condemnation that this work inspired. Despite the more muted colors from aging and exposure, the work’s scale remains awe-inspiring to see in real life. The dramatic starving forms continue to express humanity’s lowest despair and highest hope.

It’s somewhat a challenge to look at the overwhelming number of controversies and current events we face today, and ask, how is this immortalized in our art? Can we still immortalize it? Should we?

.

.

On the topic of art and contemporary history: we were also lucky to catch “Louvre Couture – Art and Fashion: Statement Pieces”. The temporary exhibition showcased apparel and accessories from 45 fashion houses like Chanel, Givenchy, and Louis Vuitton.

Louvre Couture stages a dialogue between different masterpieces through the centuries. The gilded frames and complex tapestries of the old apartments appear to mirror the embroidery and detail of the more contemporary apparel.

Is it an excess in fashion and living, justified by the fact of art?

.

.

It’s impossible to really appreciate all that the Louvre has to offer in one day. I envy French residents who have the chance to visit this place more than once a year. And how I envy the students of Europe –visitors aged 26 and below can freely visit!

But I do count myself incredibly privileged to appreciate what I used to only read about online, and I’ll be even luckier to still revisit this museum in the future.

.

.

Musée d’Orsay

Back in the summer of 2017, we spent one day in Paris walking around 20 kilometers and some change. Or maybe it was 20,000 steps. Whatever the case, I remember we walked along the bank of the Seine river and passed by the long stretch of Musée d’Orsay.

I remember telling myself: I’ll be back to visit some day.

And so here we are! The museum houses the largest collection of impressionist and post-impressionist masterpieces in the world. But even outside of that, the museum sits inside a beautiful testament to art and architectural history. Gare d’Orsay, a grand train station, previously hosted the 1900 Paris Exposition. It features a stunning steel and glass arch which perfectly frames the art underneath.

Visiting d’Orsay can easily take up a whole morning, but it’s certainly more manageable and kinder on the feet than the Louvre. The guide for general visitors also includes some highlights per floor.

One of the highlights is this sculpture by Carpeaux, which depicts four women representing Africa, America, Asia and Europe holding up the world. His work is fluidity in revolution, which to me is more visually interesting than the neoclassical posed works also featured in the first floor.

I especially loved to see the metal warmed by the sun through the building’s glass roof. An interesting detail to this sculpture, which is unfortunately on the other side from this photo, is America stepping on the broken chains of slavery around Africa’s foot.

.

.

The layout of the museum can get a little confusing. There’s a tendency to double back to see some of the inner galleries. But it kind of creates this treasure hunt vibe. It even sets up surprising scenes like this set of primary school students on a field trip.

I remember being in elementary school and going to the Manila City Hall, Fire Station, and Central Post Office for our field trip. We might have visited the National Museum.

.

.

I do remember hating on the National Museum a lot when I started visited it for a field trip back in high school. I raged on and on about the poor lighting and the disappointing facilities. Some pieces weren’t labeled. Or whatever. It was just a little frustrating moment for my teenage self.

But I’ve matured enough over the years to actually appreciate the art itself. And also to contextualize the reality of why there’s little to no investment in the arts.

Even though today I still think we deserve better (there’s no cafe or gift shop for one thing), I’m trying to stop this “deficit thinking”. I’ve realized there’s been growth, and there will continue to be growth. A lot has changed in the last 20 or so years, even if it feels a little slow for an entitled visitor like me.

That was a tangent. Back to Museé d’Orsay.

Painting a moment and a feeling

Here’s to the realists, the impressionists and the post-impressionists in Museé d’Orsay.

The first floor of the museum showcases several large canvases. Large-scale and technically detailed works such as Thomas Couture’s Romains de la décadence take up area and immerse the viewer in the scene. Before the advent of moving pictures and cinema, these works were a major source of public entertainment.

One of my favorite pieces was Courbet’s L’Atelier du peintre (1855), fully titled “The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory Summing Up Seven Years of My Life as an Artist“. I’m trying to imagine seeing this in real time, in real life, when it first came out. It must have sparked so much conversation.

For a realist’s work, it challenges what allegory and representation mean. There’s a cheeky self-portrait meta moment going on. It shows the range of the painter’s inspiration –depictions of the common country life, the bright central landscape, and then the wealthy patrons to the right.

It’s the whole world coming to me to be painted. On the right, all the shareholders, by that I mean friends, fellow workers, art lovers. On the left is the other world of everyday life, the masses, wretchedness, poverty, wealth, the exploited and the exploiters, people who make a living from death.

Gustave Courbet

His painting only highlights what it means to paint art in the context of history.

.

.

Courbet’s work is also a good example of meta-painting, specifically of a painting within a painting. That is currently my favorite type of representational art in the classic western tradition. Stop me from repeating that for the rest of this blog post.

One specific type of meta-painting I find so captivating include the ‘cabinet of curiosities’ or ‘gallery painting’ scenes. I was so happy to see this new acquisition, The Salon of 1874. Let me bring a print home, please.

Excerpt from description: “In this singular painting, not only were the works they are looking at actually shown on its wall, but the six miniature reproductions in the background were executed on canvas, before the exhibition, by the artists themselves.” This seven-handed painting features the works of E. Petite, J. Veyrassat, E. Guillemer, J. Corot, L. Richet, and H. Brown.

.

.

The upper floors of Museé d’Orsay features what most people consider the most canonical works of impressionism and post-impressionism, from Degas, Manet, Monet, and obviously, Van Gogh.

The level of technique needed to create impressionist works –extracting feeling and atmosphere through visible and short brushstrokes, focusing on the impression and not the detail– is so impressive. It’s like trying to capture the essence of a 1-hour video through a screenshot. Without the proper technique or interplay of light and color, the snapshot ends up messy and flat.

Renoir suggests music and the low chatter of people punctuated by boisterous laughter. You can smell and feel the humidity in the air or the coolness of the breeze. And it’s just a painting!!!

To me, this crowded painting is the quintessential impressionist work. Argue with me, Monet stans.

.

.

I remember watching a documentary about Monet and being so fascinated about how is health influenced his art. The broad blurry brushstrokes aren’t just a hallmark of impressionism. They’re also a marker in his journey as a person living with bilateral cataracts (blurring of vision).

And outside of himself, his works are also obviously in conversation with nature. The focus on naturalistic forms is a highlight of the movement… It is still a dream of mine to return to France just so I can visit the gardens in Giverny, where he dreamed up many of his works.

.

.

Excerpt from description: In 1920, the painter himself recounted what had happened to the picture: “I had to pay my rent, I gave it to the landlord as security and he rolled it up and put in the cellar. When I finally had enough money to get it back, as you can see, it had gone mouldy.”

Monet got the painting back in 1884, cut it up, and kept only three fragments. The third has now disappeared.

.

.

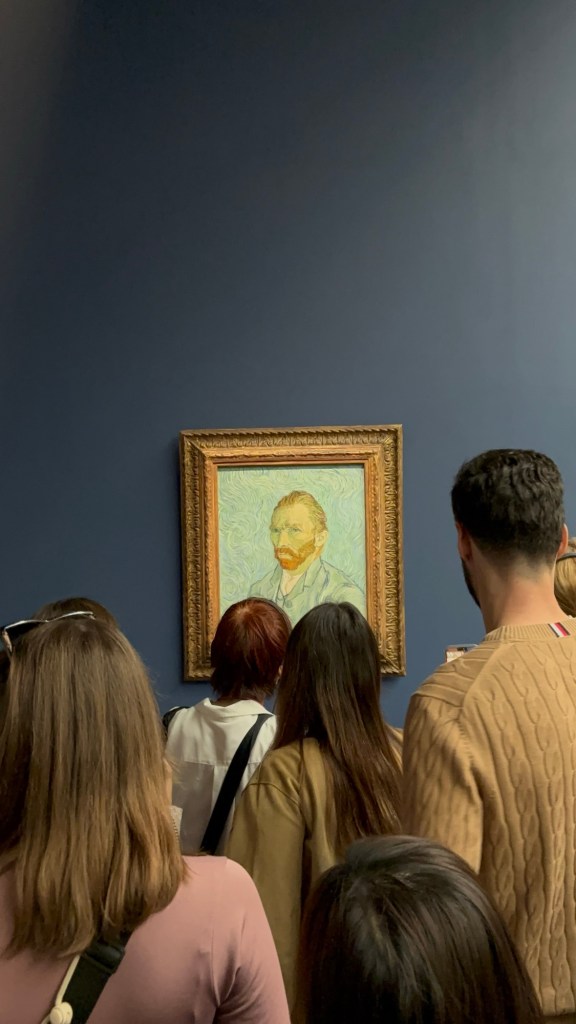

From impressionism to post-impressionism forms, maybe no one is as famous as Van Gogh. The Van Gogh I love the most remains the Sunflowers we saw in the National Gallery. Something about that bright yellow canvas in contrast with the dull wall captures my imagination up to this day. But his other works in Museé d’Orsay are no joke (when will I get inside the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam).

I love love. And I enjoyed seeing my sister fall a little in love with Van Gogh’s portraiture. The persistent crowd around his works also reminded me of that iconic scene from Doctor Who. If you know, you know.

.

.

Aside from the personal resonance of any work featuring sleep or siesta as a motif, I also liked this piece for being part of a conversation. This painting is in conversation with Jean-François Millet’s “Four Moments in the Day” series. It’s a simple genre scene that becomes more beautiful in context.

.

.

Museo Nacional del Prado

I have a distinct memory of writing an art report based on a painting Museo Nacional del Prado in 2010. That report is lost to time and my ancient laptop. But in the years that followed, I was wondering why I had no photos or other documentation of my first visit.

It turns out that apparently you couldn’t take photos inside Prado then, and you still couldn’t take any photos now. I forgot all about that rule. That’s why I really can’t recall much aside from the vivid and inescapable works of Hieronymus Bosch. But then also I was just 15. I just don’t remember anything.

So the funniest and funnest part of visiting Prado was trying to document it. I do have some, maybe, don’t quote me on that. But it was a little side challenge for me and my sister.

In this photo: Aniceto Marinas’ Statue of Velázquez. It’s a tribute to the great Spanish baroque painter who led the court of Spain and Portugal in the 17th century.

.

.

The hard rule against photography is really for the protection of the art. It reduces the odds of flash lighting damaging the paintings.

The Prado’s commitment to preservation is also reflected in their art restoration efforts. Compared to the sometimes dusty, dull or cracked varnish of paintings at the Louvre, the paintings in Prado were more vibrant and true to original color.

There’s also a strong industry of art reproductions in Prado. We saw at least two or three local artists creating faithful reproductions of licensed masterpieces. It was a privilege to see good painters work on their craft. The act of recreation prompts even more appreciation of the original art.

I have two clear favorites in my head, that I may or may not have a photo with. The first was David with the Head of Goliath, attributed to Caravaggio (ca. 1600). I think it’s quite underrated, but definitely not for me and my family. Chiaroscuro seems at its best in this baroque painting. It’s one of the most striking biblical paintings I’ve ever seen –with clear action and contrast similar to Judith Beheading Holofernes, also by Caravaggio.

My second favorite circles back to my new love of meta-paintings. The background of Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez features works by Peter Paul Rubens. It was a sign of great respect to the relationship of these two masters. Aside from that narrative, the painting also challenges the viewer by using an innovative perspective. It takes contemplation and wonder to even guess at the center of the composition, and therefore its meaning.

I’ve read and watched videos on Las Meninas before, but it never stood out for me. My interest was mostly academic. But when I entered that big hall, with the painting at the center (and a security guard patrolling for errant cameras), I was really quite impressed.

It just goes to show that seeing art in real life, and visiting it in the context of other works, can change so much about understanding.

Since I could not properly take any photos or videos with commentary, I mostly had to rely on my travel journal to record my thoughts. Luckily, the museum of Prado is quite well-stocked, so I brought home many postcards and small prints.

.

.

Architecture as art, the streets as museum

We were a little aimless when we took a side trip to Toledo, Spain. Luckily, it brought us to the Museo de Santa Cruz (which also had free admission). The museum featured an eclectic mix of art, archaeology and ethnographic pieces, even including azulejos or porcelain tiles from Portugal. There was a strong collection of El Greco paintings, which I did appreciate a little.

But the museum itself was a work of art. The space evoked the same wonder, contemplation, and pleasure of living. What a blessing it was to walk down its halls and hold the old balustrades.

The building has stood so beautifully for generations, beginning as the Hospital of Santa Cruz in the 15th century, and yet it has retained an addicting blend of Moorish/Mudéjar and Renaissance architectural traditions.

Can I have this at home, please?

.

.

.

.

I believe I read Don Quixote some time in elementary, but it must have been way above my literacy skills because I don’t remember anything outside the synopsis. Time to read it again (maybe in its original Spanish?)

.

.

Until death it is all life.

Miguel de Cervantes

Before I end this blog post –and likely, take a long hiatus before any new posts from our Europe trip– I want take time to appreciate the art that lives in the streets of Spain. Not to romanticize our oldest colonizer, but more to recognize that they have the privilege and the will to see their old works maintained and commemorated.

Even the cobblestones are preserved. Train stations and parking lots were moved underground so they don’t destroy the skyline and disrupt pedestrians. They put premium on old facades and harmonious urbanization.

The balancing act between innovation and cultural preservation can be so beautiful when done right. It fosters love for a place. It builds character.

*Madrid installs golden plaques in front of establishments that have been in business for at least a century (seen a little here). Provided: it’s the same business name, same offered service, and with continuity of ownership in the same family.

.

.

And if we’re going to talk about art in the streets or the city as a work of art, then I can’t end this post without mentioning Barcelona. Antoni Gaudí‘s city shines with the love he poured into it.

Maybe I’ll make a separate post for the places we saw: Parc Güell, Casa Batlló, Casa Milà, and of course the Sagrada Familia. Each building and curved bench was Gaudí defining Catalan Modernisme.

What really strikes me even as I write this is how you can feel his passion for architecture, nature, and religion. The organic forms, the philosophy of quality, and the spirituality that underpins the mastery –it’s difficult to describe in words. It renders me speechless in real life.

Nothing is art if it does not come from nature.

Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926)

Projections did say the final vision may be complete by 2026.

I will definitely have to return when it is completed (and perhaps also visit Casa Vicens Gaudí, among other places).

For those planning to visit: yes, it’s worth it.

.

.

A rainbow of light streaming through stained glass, a forest of columns holding up the sky of God… isn’t the creation of this beauty what our hands were made to do?

Until next time! ♥

Say something back.